[Hikawa Ryusuke’s “Anime has a history”] The origins of Yamato’s journey over half a century

(C) Tohokushinsha Publishing/Chief editor: Akio Nishizaki

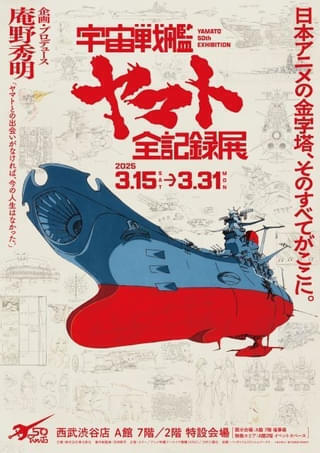

The “Space Battleship Yamato Complete Records Exhibition, Planned and Produced by Anno Hideaki/Celebrating the 50th Anniversary of Broadcast” will be held at Seibu Shibuya from March 15th (until March 31st). The subject of the exhibition, “Space Battleship Yamato,” is a monumental TV anime that changed the history of Japanese animation (aired in 26 episodes from October 6th, 1974 to March 30th, 1975). It became a huge hit when it was re-edited and released as a theatrical version in 1977. It was the catalyst for the transformation of “TV cartoons” for children into “anime” targeted at teens and above, and became the origin of anime culture that continues to this day. A major feature of this exhibition is that it focuses on “raw materials” such as existing “proposals,” “setting materials,” “storyboards,” “original drawings,” and “art boards.” It is a groundbreaking opportunity to see intermediate productions in pencil and paint form, rather than working copies or printed materials. The organization of the archive was led by the certified nonprofit organization Anime and Special Effects Archive Organization (ATAC), and many of the original drawings and cels were provided by fans who, like the author, had been in their personal collections for many years. It is a comprehensive work worthy of a work that created a boom when the production team and fans came together. The author’s materials have already been donated to ATAC. This is also linked to the Agency for Cultural Affairs’ ongoing efforts to preserve, store, and utilize the intermediate products of media art works such as manga, anime, special effects, and games, as well as to passing them on to the next generation and promoting culture and the arts. In November 1974, when I was a second-year high school student, I visited the Office Academy Studio in Sakuradai, Nerima Ward, where Space Battleship Yamato was being produced, and was deeply impressed. In particular, the setting manual, which I saw for the first time, was so large that it completely changed the way I looked at anime. At a time when anime magazines had not yet been published, I did not fully understand the existence of a “blueprint for unifying the art” until I saw the real thing. Born in the “TV cartoon era,” “Space Battleship Yamato” was something out of the ordinary. It was an anomaly, an anomaly for its time. And as I saw the documents and other painstaking but detailed processes in the studio, and then talked to the staff, I realized that there was a reason why a work that I thought was great became great. This intellectual curiosity has continued to energize my work for the past half century. I am not ignoring the evaluation of the footage and prioritizing the documents. I was shocked by the very existence of the “basis.” And if the information incorporated into the footage, the way it was constructed, and the process are what make it great, I thought this could be analyzed from an engineering perspective. Later, when I got a job at a manufacturer and began to develop IT equipment and create value, I became convinced that “if I know how to analyze it, I can use it in other industrial work,” and I was able to achieve some results in my 18 years as an engineer. So what was the value of “Space Battleship Yamato”? For me, it was the “attractive force that makes you unable to take your eyes off it” that emanated from the footage. And the “pressure that makes you believe in the existence of people who take action” increases in sync with the story’s progress from within the “Yamato world.” This is what gives the drama its great value. If this phenomenon occurs in a drama alone, it should also occur in novels and manga, so this is also the “reason for taking so much time and effort to make it into an anime.” The methodology is diverse because it is a comprehensive art. One of them is “depiction based on the basis of the setting” (there are many others, but I will omit them this time). I have read making-of articles from before “Yamato,” but perhaps because it was aimed at children, I only saw it as “the drawings were done by dividing up the work somehow.” I didn’t even understand the simple fact that “meaning and pressure are worked into” based on solid grounds and instructions, and I often doubt whether this point is still shared in 2025. What I want you to pay attention to this time is the extraordinary quality and density of the mecha-related settings in “Yamato.” Many of the designs were created through a collaboration between Matsumoto Reiji, who was in charge of direction, setting, and design, and the design company Studio Nue (Miyatake Kazutaka, Kato Naoyuki, Matsuzaki Kenichi). Both creators are manga and illustrators, so even the line drawings can be appreciated as beautiful single images. From the perspective of the aforementioned “basis,” look at the complexity of the “structure” incorporated in the design. The essence of anime is “exaggeration and omission,” but this is the exact opposite. For Yamato itself, the beauty lies in where the curvature of the hull changes, with “bulges” and “waists” beautifully depicted, and it makes sense why “ships” are referred to as feminine pronouns in English-speaking countries. However, this was also a delicate task that was not well suited to collaboration. The original role of settings is “unity.” It has a mission to “communicate the shape so that it can be recognized as the same overall, regardless of the animator’s hand.” The reason why the mecha designs of the “TV cartoon era” often consisted of combinations of cubes, cylinders, spheres, etc. is because the shapes were easy to create and uniform. To begin with, the Yamato body has an excessive number of lines. This was a terrible omen for animation, and there is even a legend that an animator who was commissioned to do the work ran away. For example, the bank cut, which was used almost every week, in which Yamato approaches from the distance, crosses in front of the camera, then goes back into the screen again, used about 250 frames of video. This means that a single line drawn in the design was multiplied by 250 times. However, there is a good reason for the number of lines, and it is important to note that this reason also brings “pressure” to the screen. If you look at the Wave Motion Gun, you can see that the inside of the funnel-shaped muzzle has uneven grooves carved into it, and the caliber itself becomes thinner as it goes deeper. This groove is a design that is reminiscent of the “rifling” that is carved into the inside of a real-world gun or cannon bullet to increase the straightness of the trajectory when it is fired, and that is why there are so many lines. Such grooves may not be necessary for a wave motion gun that fires tachyon particles, but it is a design that enhances the ship’s “uniqueness.” The onboard structures, modeled after the Yamato battleship, are also extremely complex. There are main and secondary guns, a bridge, antennas, machine guns lined up on both sides, funnels, catapults, and even stabilizing wings, with slits everywhere. All of these have a combat role and are positioned three-dimensionally, so they cannot be omitted. When Yamato “turns,” the changes in the relative positions of all the parts must be calculated and deployed one by one into moving pictures. This is a difficult task, but if it is successful, the transition of the three-dimensional structure will make Yamato’s presence more believable, as in the opening cut where the ship retreats from the first bridge and slips past the main gun to reveal the whole picture. The interior of the Yamato is also full of details, starting with the first bridge. But are the meters and levers placed there as decoration? No, that is not the case. The story is filled with advanced ideas that were thought out logically at the setting stage. Roles and operations are specified in detail, and the storyboards and direction interpret these to have the characters act. In other words, “functional beauty” is pursued throughout. The appeal of Yamato is its philosophy that it is ultimately humans who bring out this functional beauty, and the setting strives to highlight this. The fact that the ship’s onboard equipment, which embodies functional beauty, functioned behind the scenes to support the drama as an interface when immature young people joined forces and overcame adversity should be conveyed from the original plates lined up in the exhibition. It would be my greatest pleasure if you could enjoy this discovery, which is connected to the shock I felt when I was 16 years old. Another highlight of this exhibition is the original animation drawings. In March 1975, I used my spring break to visit various studios that were nearing the end of production and rescued many original drawings that were about to be sent to the paper recycling center. Next, when the main Sakuradai Studio was closed, we asked the setting production team to collect many of the intermediate works that were no longer needed. All of this was done based on the conviction that “it would be a national loss if these were to disappear, and they are worthy of being placed in a museum someday,” so it is a little different from a collection. Half a century has passed, and it is moving that we have finally reached a stage where this feeling can be proven. The original drawings before corrections are filled with a unique spirit. In the next process, the animation, the lines are cleaned up with clean lines, but the lines are drawn with varying thicknesses that allow the movement to be read, which also serves as instructions for this. The original drawings contain a lot of information that conveys the animator’s feelings, such as the pressure and brushstrokes used to draw them. After the broadcast, the collected materials were arranged in groups with cels, original drawings, settings, and storyboards. Because the cels deteriorate, they were taken out of the cutting bags, the sheets were read and assembled, the frames were cut, and they were photographed as still images, but later it became clear that this was similar to the work of an assistant director. Furthermore, even after the broadcast, I followed up with Chief Director Noboru Ishiguro, interviewed him, and analyzed for myself the reasons why it was so amazing. In an era when there were no anime magazines, thinking and acting for myself became the starting point of my anime research. For me, this is a “miracle exhibition.” I apologize for including some personal feelings, but I have tried to explain why it is a “miracle,” and to explain a small part of what I would like you to think about when you stand one-on-one in front of the original drawings. I would like you to reset the miscellaneous information you have gained from magazines and the Internet over the past half century, and receive the “pressure” of the original drawings with an empty mind. This is a rare opportunity to celebrate the 50th anniversary. It is a great chance to go back to the heart of half a century ago and relive what it was like. Doing so will not only help you to look back, but will also naturally give you a positive outlook on what the future holds. I hope that something new will start from there (titles omitted). × × ×[Additional Note] My book “Fantasy Visual Culture Theory: From the Kaiju Boom to Space Battleship Yamato” (KADOKAWA) will be released on March 12th. The cover features Yasuhiko Yoshikazu’s “Space Battleship Yamato”, and the recommendation on the obi is by Anno Hideaki. I am very grateful. It is an attempt to look at what the “TV cartoon era” leading up to “Yamato” was, taking an overview of the situation including not only anime but also monster stuff (special effects) as “fantasy visual culture”, and discovering new cultural aspects from its comprehensiveness. I look forward to hearing from you.

Hikawa Ryusuke’s “Anime has a history”

[About the author]

Hikawa Ryusuke

Born in 1958. Anime and special effects researcher. 41 years have passed since his debut the year before the monthly anime magazine was launched. After graduating from the Tokyo Institute of Technology, he worked as a communications device engineer at an electronics manufacturer before becoming a full-time writer. He has served as a judge in the animation division of the Japan Media Arts Festival and the Mainichi Film Awards.

Comment